There are different forms and treatments of subordination agreements in Swiss insolvency. This article is inspired by the authors’ experience representing the security agent of $1.75 billion bond issue of a Swiss based oil refinery group

1 Minute read |

Subordination agreements are frequently used in cross-border financing transactions to determine the priority ranking among creditors. In addition, so-called general subordination is a key instrument provided for under Swiss company law (article 725 II of the Swiss Code of Obligations) to enable the restructuring of distressed companies. Although the treatment of general subordination in Swiss insolvency proceedings is undisputed, this is not the case for other forms of contractual subordination, which benefit only specific creditors. Where relative subordination is agreed, the extent of its enforceability might thus depend on the specific contractual arrangement between senior and subordinated creditors. |

When a group of lenders extends credit to the same borrower, it usually enters into an intercreditor agreement, a key component of which is a subordination provision setting out the ranking and priority of repayment rights. In addition, the subordination of intragroup funding, ie loan agreements between group companies, to the lenders' claims is frequently seen in financing transactions. In Switzerland, subordination agreements also serve as an instrument under company law (article 725 II Swiss Code of Obligations (CO)) that enables over-indebted companies to continue doing business. The subordination clauses as seen in the intercreditor agreements or other debt financing structures on the one hand (Nachrangigkeit) and subordination agreements satisfying the requirements of article 725 II CO (Rangrücktritt) on the other serve different purposes and need to be carefully distinguished. Although all subordination agreements are concluded with a view to a possible insolvency of the borrower, their effect and enforceability in Swiss insolvency proceedings is only clear if falling under article 725 II CO, whereas the treatment of other contractual subordination is uncertain.

Subordination pursuant to article 725 II CO

Under Swiss corporate law, the board of directors has to take specific measures if the company finds itself in distress. These measures include a duty to notify the bankruptcy court, if a company suffers from a capital deficit to the extent that the claims of the company's creditors are no longer covered, whether the assets are appraised at going concern or liquidation values (over-indebtedness). The board of directors can refrain from notifying the judge, if a creditor subordinates its claims in the amount of the capital deficit to all other liabilities pursuant to article 725 II CO. There is no need for the board of directors to obtain approval from the other creditors or the shareholders. By subordinating their claims, creditors agree that, if insolvency proceedings are opened over the borrower company, dividend distributions will only be paid out to them if and after all other unsubordinated and unsecured claims are satisfied in full.

|

|

An assignment of the subordinated claim is not mandatory to give effect to the relative subordination |

|

|

An agreement to subordinate a claim does not constitute a waiver. The borrower company must continue to account for subordinated claims as liabilities and disclose the subordinated loan separately in the annual financial statements. Accordingly, the subordination itself does not constitute a restructuring measure since the financial situation of the company remains unchanged. However, subordination agreements increase the chances for a distressed company to financially recover as they allow for more time to adopt restructuring measures. Subordinated loans pursuant to article 725 II CO have in practice often been used as de facto equity surrogates for many years, although this is not the intention of the law. It is important to note that the Swiss Federal Supreme Court held that subordinated claims are to be included in the calculation of damage when ruling on a director's liability claim.

The law stipulates that the board of directors can only refrain from notifying the judge if the amount of subordinated claims equals or exceeds the capital deficit. The wording of article 725 II CO does not indicate whether the deficit should be appraised at going concern or liquidation values for the purposes of determining the necessary subordination amount. The question is controversially discussed. Some authors argue that in addition to the capital deficit the subordination amount should cover at least part of the share capital. A 2003 judgment of the Swiss Federal Supreme Court dealing with the termination of a subordination agreement, indicates that it is admissible to appraise assets at going concern value if the company is expected to overcome the state of over-indebtedness. If this is not the case, for example due to the company's liquidity problems, accounting on a going concern basis is no longer permitted. In such a case, the extent of the subordination of claims required needs to be calculated at liquidation values, which usually makes restructuring impossible. The going concern statement of the auditors is paying an important role in the termination of the subordination and any restructurings.

Legal doctrine and case law have determined that any subordination agreement needs to include a deferral agreement, at least with regards to the principal amount of the loan, as well as a prohibition for the borrower to repay or set off the subordinated liabilities. If it were possible to satisfy the subordinated creditor before insolvency, this would jeopardise the purpose of article 725 II CO to improve the borrower's financial situation, and the position of the other unsubordinated and unsecured creditors. The declaration to subordinate must further be irrevocable, unconditional and unlimited in time (although termination is possible under the requirements explained below) to meet the requirements of article 725 II CO. Finally, the claim covered by subordination may not be collateralised with assets of the borrower.

The subordination agreement can only be terminated once the borrower company is no longer over-indebted, which may be assessed on a going concern basis. Until then, the subordination agreement remains effective, according to the Federal Supreme Court.

Subordination agreements in debt financing – relative subordination

In addition to the subordination pursuant to article 725 II CO, which constitutes a company law instrument and may enable restructuring measures, subordination agreements can serve to secure the payment of debt owed to one or more specific creditors and are most commonly used in the context of financing transactions. Since the subordination according to article 725 II CO benefits all other creditors, it is often referred to as general subordination. This is in contrast to the subordination agreements intended to benefit only specific lenders, ie provide for relative subordination. If the subordination is not intended to have the effect of article 725 II CO, it does not have to fulfil the requirements described above. In most cases though, a subordination agreement will contain a deferral as well as a prohibition of repayment or set off, to ensure the intended effect of the subordination. In addition, the subordinated creditor might assign its claim to the senior creditor. However, such assignment of the subordinated claim is not mandatory to give effect to the relative subordination.

Subordination provisions in intercreditor agreements

Intercreditor agreements determine the ranking between the lenders of a syndicated loan including provisions on payment seniority, security interest priority and contractual subordination (payment waterfall or application of proceeds).

The basic premise of intercreditor agreements including mezzanine and senior debt financings is that mezzanine debt is subordinated in right of payment to senior debt. The borrower is usually blocked from paying the mezzanine debt and the mezzanine creditors are prohibited from exercising remedies against the borrower. The intercreditor agreement may also contain a provision, by which the mezzanine creditor is required to turn over any amounts they receive but are not entitled to under the intercreditor agreement, to the agent for application in accordance with the payment waterfall. As it is generally the agent's responsibility to receive payments from the borrower and distribute them to the parties in accordance with the intercreditor agreement, the enforceability of such subordination provisions in Swiss insolvency proceedings (namely their consideration ex officio by liquidators), is of limited relevance.

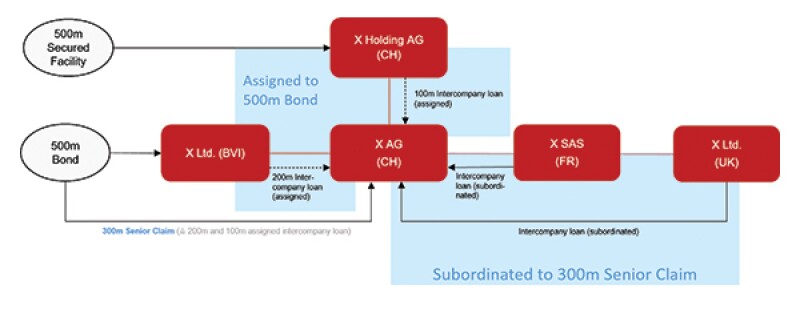

Subordination of intercompany loans

If a company requires capital beyond what they are able or wish to obtain through the standard syndicated loan they may enter into an additional financing transaction. A company may combine a syndicated loan with a high yield bond. In simplified terms, such a structure might look as follows (see illustration above): a group of companies, ie their holding company X Holding AG, receives financing from a bank syndicate under a credit facility. In addition, the group's finance company, X Ltd, as an example, issues bonds at a later stage, the proceeds of which are distributed within the group through various intercompany claims. Normally, all of the group's assets are assigned as collateral to the bank syndicate – with the exception of the intercompany loans. These intercompany claims remain the only asset available to provide security for the bondholders. Intercompany claims are frequently not assigned to the bank syndicate because re-assignment for restructuring purposes requires the consent of all, or at least the majority, of banks. For the same reasons, the assignment as security of all intercompany claims in favour of the bondholders is not desirable from the borrower's perspective. In our example, a couple of intercompany loans into the same group company – X AG – are assigned as security to the bondholder agent and constitute the senior claim of the bondholders into X AG. In addition, some group companies agree to subordinate their (current and future) intercompany claims against that same company, X AG, in favour of the senior claim, to prevent that additional intercompany indebtedness of X AG impair the value of the bondholders' security, ie the senior claim, in the event of insolvency.

The relevant missing element, if intercompany loans are subordinated to secure the obligation under a separate second financing transaction, is that there is no intercreditor agreement between the subordinated intra-group companies and the senior lenders of the second financing transaction.

Enforcement of subordination in Swiss insolvency proceedings

Subordination agreements are subject to the choice of law. If insolvency proceedings, ie bankruptcy or composition proceedings, are opened over a company domiciled in Switzerland, these proceedings are governed by Swiss law. Therefore, if the question arises as to whether a subordination agreement is valid and how it is to be qualified, foreign law may apply – often English law. The question of how subordinated claims are to be dealt with in Swiss insolvency proceedings is governed by Swiss law, namely the Swiss Debt Enforcement and Bankruptcy Law (DEBL).

Creditor rankings in Swiss insolvency proceedings

In Swiss insolvency proceedings, all claims are ranked as follows:

Estate claims (Masseverbindlichkeiten) consist of claims arising out of transactions entered into after the opening of insolvency proceedings as well as the costs of conducting the proceedings and are satisfied with priority before any distributions are made to other creditors.

Secured claims (pfandgesicherte Forderungen) are satisfied on a priority basis from the proceeds of the disposal of the security. If these proceeds are not sufficient to satisfy the entire secured claim, the uncovered amount ranks as unsecured claim.

Unsecured claims are divided into three classes:

The first class of claims mainly consists of claims arising from employment relationships.

The second class encompasses claims from social security.

The third class comprises all other unsecured and unsubordinated claims.

Dividend distributions are made according to the creditors' ranking. Claims in a lower ranking class will only receive dividend payments if all claims in a higher ranking class have been satisfied in full. If the insolvency estate does not have enough funds to cover all claims in one class, the proceeds are distributed to the creditors of that class on a pro rata basis according to the claim amounts. The division of unsecured creditors into three classes is binding for the liquidators. A contractual subordination, by which a creditor agrees to have his claim satisfied only after specific or all other claims are satisfied needs to be dealt within the legal ranking system of the DEBL.

Enforcement of subordination pursuant to article 725 II CO

In prevailing doctrine there is a consent that the liquidators in a bankruptcy or composition proceeding have to enforce a subordination pursuant to article 725 II CO ex officio. Generally, the liquidator admits or rejects a creditor's claim in a schedule of claims and accordingly prepares a distribution plan. Although the effect of a subordination agreement will not materialise before the stage of dividend distribution, as it can only then be determined whether the claims of the beneficiaries will be fully satisfied, the liquidators have to include their decision on the admittance of the subordinated claim and the validity of the subordination agreement in the schedule of claims. If the subordination is accepted by the liquidators, the subordinated creditor only receives dividend distributions, if there are sufficient funds in the insolvency estate to satisfy the claims of the beneficiaries. In the case of a subordination agreement pursuant to article 725 II CO, all other unsubordinated creditors will benefit from the subordination – the subordinated creditor will in most cases not receive any distributions.

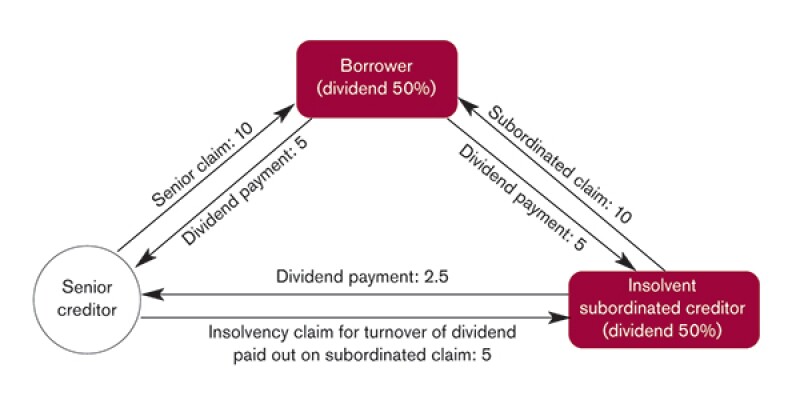

Enforcement of relative subordination

Whether a liquidator also has to consider a subordination agreement which only benefits specific creditors (relative subordination) ex officio is controversially discussed. Some authors and liquidators argue that a claim which is relatively subordinated, should be admitted in the schedule of claims like a normal claim and dividend payments made to the subordinated creditor. According to prevailing opinion, however, relative subordination should be enforced by the liquidator just like subordination pursuant to article 725 II CO. In this case, the dividend accruing to the subordinated creditor would not be paid out to the subordinated creditor but directly to the senior creditor (in addition to the senior creditor's own dividend) until the senior claim was paid in full. After the senior creditor has been paid, the remainder of the subordinated creditor's dividend would be paid toward the subordinated creditor's own claim.

This discussion also becomes relevant if parties have to enforce the subordination agreement in court. If the subordination is to be admitted or rejected in the schedule of claims ex officio, any disagreement between the parties about its validity or its extent must be settled by means of an action to contest the schedule of claims. Such litigation takes place in Switzerland, where insolvency proceedings were commenced. If on the contrary, the liquidator does not have to take the subordination into account, the senior creditor would have to file an action against the subordinated creditor to turn over dividend distributions, ie a normal action for payment outside insolvency proceedings.

In cases where the subordination has been agreed to in an intercreditor agreement, the senior creditors are not as dependent on the liquidator to decide on the subordination in the schedule of claims. If the liquidators ignore the relative subordination and make distributions to the subordinated creditor, the latter would have to turn over such distributions to the agent for application of proceeds. Hence, the senior creditors may assert their claims under the subordination clause against the subordinated creditor or the agent.

The situation is different if a company raises funds through two separate financing transactions, and intercompany loans (or other claims) are subordinated to secure repayment of the second transaction. As explained, in such structures the senior creditors are not party to an intercreditor agreement and thus cannot rely on an agent to apply proceeds according to a waterfall provision. Further, in most cases the entire group of companies becomes insolvent, thus not only the borrower but also the subordinated creditors. If the Swiss liquidator does not have to decide on the relative subordination ex officio, the bondholders would potentially have to initiate separate litigation against all the subordinated creditors in their respective jurisdictions. Although the subordination agreement will usually contain a jurisdiction clause, claims against insolvent subordinated creditors have to be filed where they were domiciled. This would increase the risk of conflicting interpretations of the subordination agreement by the respective courts, while coordination in Switzerland in the context of the same insolvency proceedings would be much simpler and more practical.

|

|

Whether a Swiss liquidator has to consider relative subordination ex officio is controversially discussed |

|

|

In case of insolvency of the whole group, there is also a risk of claim dilution should the subordination not be enforced by the liquidator and the senior creditor not be able to rely on an intercreditor agreement (see illustration below). If the subordinated creditor becomes insolvent as well, the senior creditor will have to file their claim for turnover of dividends paid to the subordinated creditor by the borrower as an insolvency claim. Should the senior creditor prevail, they can only expect a (further) dividend payment from the insolvency estate of the subordinated creditor. That dividend payment will be calculated on the basis of the dividend the subordinated creditor received from the borrower's insolvency estate. Thus, senior creditors can only expect to receive a dividend on the dividend.

As of today, Swiss courts have not had the opportunity to address the question of whether a liquidator is under an obligation to take into account an agreement providing for relative subordination to the benefit of specific creditors. As long as the Swiss Federal Supreme Court has not issued a judgment in this respect, the enforceability of a relative subordination agreement, as often used in financing transactions, in Swiss insolvency proceedings is uncertain. In addition, it is controversially discussed whether the senior creditor has a right to file the subordinated claim in the insolvency proceedings on behalf of the subordinated creditor. Some authors oppose this view, arguing that the senior creditor is only left with a compensation claim against the subordinated creditor, should the latter refrain from filing his claim. For all these reasons, alternative mechanisms to a relative subordination should be considered in transactions involving Swiss companies.

The benefits of a relative subordination might be achieved through an assignment of the claim by way of security. The enforceability of a security assignment in insolvency proceedings is undisputed and has been confirmed by the Swiss Federal Supreme Court. In addition, the assignee is not dependent on the assignor to actually file the claim, as they himself become the claimant. As explained above, with respect to intercompany claims an assignment is generally avoided deliberately, as this restricts a group's future restructuring possibilities and the work of the finance department. To avoid this, the effectiveness of the assignment could be made conditional upon the insolvency of the borrower. As there is an increased risk in an intra-group context, that the subordinated creditor become insolvent around the same time as the borrower, parties should bear in mind the risk of claw-back actions in the insolvency of the subordinated debtor.

Conclusion

Given the important role subordination agreements play in the context of financing transactions, the enforceability of not only general but also relative subordination in Swiss insolvency proceedings would be desirable, in order to not restrict their use. The relevance of this discussion is limited in standardised transactions including an intercreditor agreement, as the subordination can be enforced by means of the agent. However, the relative subordination of intercompany loans is also a common structuring possibility in financing transaction. In these cases, senior creditors need to rely on the liquidator to enforce the payment waterfall or might face proceedings in several jurisdictions and risk a dilution of their claims, if the subordinated creditor became insolvent as well. Until the Swiss Federal Supreme Court decides the matter, this useful tool should be employed with caution. A conditioned security assignment as described above should be considered in addition to a subordination agreement.

About the author |

||

|

|

Daniel Hayek Partner Zurich, Switzerland T: +41 44 254 55 55 E: daniel.hayek@prager-dreifuss.com Daniel Hayek is a member of the management committee and head of the Insolvency and Restructuring team as well as the Corporate and M&A team of Prager Dreifuss, one of Switzerland's leading firms for commercial law. His practice focuses on all aspects of insolvency and restructuring including representing creditors in bankruptcy-related litigation, registering or purchasing claims or in enforcing disputed claims before courts. His longstanding expertise includes M&A, corporate finance, takeovers, banking and finance and corporate matters also in restructuring situations. |

About the author |

||

|

|

Chantal Joris Junior associate Zurich, Switzerland T: +41 44 254 55 55 E: chantal.joris@prager-dreifuss.com Chantal Joris is a junior associate at Prager Dreifuss. Her main practice areas are corporate and M&A and litigation & arbitration. She focuses mainly on contract and corporate law matters as well as insolvency law and acts for national as well as international companies. Further, she concentrates on legal aspects of information technology and data protection. |