What makes Islamic finance different from conventional finance?

A common misconception is that Islamic finance is just banking without charging interest. Islamic finance however is concerned with the very nature of money and how it is used. Since US President Nixon’s decision to cut the link between gold and currency in 1972, it has become commonplace for money to be made out of money. Since the 1945 Bretton Woods agreement was reversed under Nixon, countries’ budget deficits have ballooned to unthinkable levels. Under Islamic finance, in a similar way to convention previous to 1972, Islamic transactions have to be underpinned by an asset. In the Islamic model, money is merely a medium of exchange and a measure of value of real goods and services.

One of the biggest differences is that Islamic finance has ethics very much at its forefront. It aims to prioritise transparency, certainty of outcome and protection of investor’s liabilities. It also does not allow investment in gambling, pornography or alcohol, among other things.

There are a multitude of different structures used in Islamic finance. Among the most common is murabaha, which is generally considered to be the Islamic framework for a conventional loan and is regarded as the most straightforward to structure. An ijara structure is the equivalent of a lease while mudarabah is like a shared investment venture. The wakala structure can be compared to an agency agreement, where the principal appoints an agent to carry out a task.

Gateway partner Harris Irfan said English law perfectly complements these structures. “It often appears superficially that there is a conflict between English and Sharia law but this is not true,” he said. “Most Islamic finance contracts are governed by English law precisely because it is so compatible with sharia.”

Al Rayan Bank treasurer Amir Firdaus said the first step is about identifying a structure that works with English law. “For example, debt structuring already exists in English law so you need to look at the Islamic structure that complements it best,” he said. “Thankfully, a lot of English law complements Islamic finance well. It is more about the processes you tend to go for.”

What is a sukuk?

Sukuk are widely thought to be Islamic bonds. But unlike a conventional bond, which is effectively a debt instrument, a sukuk is a trust certificate where there is no element of debt financing. It can be structured on an asset base or be asset backed. Sukuk are growing in popularity across Europe, the US and many jurisdictions in Asia and the Middle East. The UK government issued its first sukuk in 2014, becoming the first country outside of Muslim nations to do so and to underline the demand for these assets, the £200 million ($276.5 million) issuance receiving orders totalling £2.3 billion. The UK plans to reissue a sukuk in 2019, a move believed to be a signal that investment in this area will be accelerated after Brexit.

While countries across Europe are behind the UK, a report from Malaysia’s RHB Bank suggested that Germany is planning a $1 billion sukuk issuance in the near future. Al Rayan Bank, the first UK-based Islamic bank to receive a credit rating from Moody’s, estimates a third of its customers are not from the Muslim faith. The entire industry is expected to grow to $3.5 trillion by 2021 and western countries will have a big role to play if the industry grows to this level.

Irfan says that the structure of sukuk is particularly attractive to conventional investors. “Fixed income investors generally prefer unsecured debt obligations like a conventional bond, and most sukuk are structured this way,” he said. “As a result, they remain compatible with sharia but perhaps might not be in keeping with the true spirit of the Islamic economic model.”

Firdaus says that sukuk are particularly attractive because they tend to offer higher yields than conventional bonds and are secured. The challenges come with explaining the structure to an investor and processing the large amount of documentation involved.

“The understanding of it takes time and it is often about explaining the similarities to the conventional bond,” he said. “A conventional transaction normally has one contract that encapsulates everything. In Islamic finance there is often several contracts, because there are more than one transaction happening at the same time”.

The state of Islamic finance

Total sukuk issuances are falling, however. According to an S&P Global report, total issuances fell from just below $140 billion in 2012 to just over $60 billion in 2015. Firdaus attributes this fall to the decrease in oil prices and complacency on the part of Islamic banks which are not offering enough products to the market. It may also be due to the lack of global standards used to certify sukuk are sharia-compliant – several jurisdictions such as Malaysia, Indonesia and the Middle East dominate in terms of issuance though they don’t necessarily share the same approach when it comes to structuring and issuing sukuk.

Irfan agrees with these views, but does not believe this is an issue that cannot be corrected. “I think Islamic finance has stagnated, growth rates are not increasing as they should,” he said. “Its future lies with disruptive technologies and if we can combine Islamic finance with these, then I believe we will see a return to the exponential growth rates of the early 2000s.”

The problems mainly lie in a misunderstanding of the purpose of Islamic finance and as a result, opportunities are not being exploited. “Much of the Islamic finance industry is dominated by conventional bankers, who do not typically hold any ideological affinity to the Islamic economic model,” he said.

Because of this approach he says some people are sceptical about Islamic finance, merely seeing it as interest with another name and not truly sharia-compliant. Irfan says: “The banking industry has not done enough to convince them otherwise.”

The legal state of Islamic finance

Much of this is yet to be legally tested in the UK, but as time goes on, legal precedents are expected to become commonplace. Dana Gas, an Abu Dhabi energy firm, recently declared $700 million worth of sukuk non-sharia compliant and therefore concluded it was not obliged to repay its debt. A court case was adjourned on December 25, but everyone is the industry is keen to see whether the mudarabah contracts associated with the sukuk will be determined valid. IFLR understands that a resolution is close in favour of the debtholders.

In 2010 the Investment Dar Company (TID) refused to pay Blom Developments Bank because it did not believe the wakala agreement was sharia-compliant in the first place. The decision to allow TID’s appeal created quite a problem in the industry because people became worried that they would not follow through with their agreement.

In the previous year, Dubai real estate developer Nakheel delayed many of its projects and was unable to repay its sukuk obligations after its holding company Dubai World restructured $26 billion of debt. Bondholders were concerned that the company may have to default, but declared itself debt free in 2016 and fully repaid the sukuk when it matured.

Other than these high-profile deals, Islamic finance has largely avoided legal uncertainty though the shadow of the Dana Gas case does loom at present. It is beyond doubt that Islamic finance is becoming more common in the west, but improvements need to be made if it is to truly flourish as a mainstream financial tool outside the Middle East.

Glossary

Ijarah: A lease contract that binds both parties.

Mudharabah: Investment management partnership. One party contributes financially, the other provides expertise and all profits and losses are shared.

Murabaha: Referred to as a ‘cost plus’ contract. A financial institution purchases an asset and sells it to a customer on a deferred basis.

Musharakah: An investment partnership where all profits or losses are shared.

Qard: A loan equivalent which is required to be repaid at a pre-agreed time.

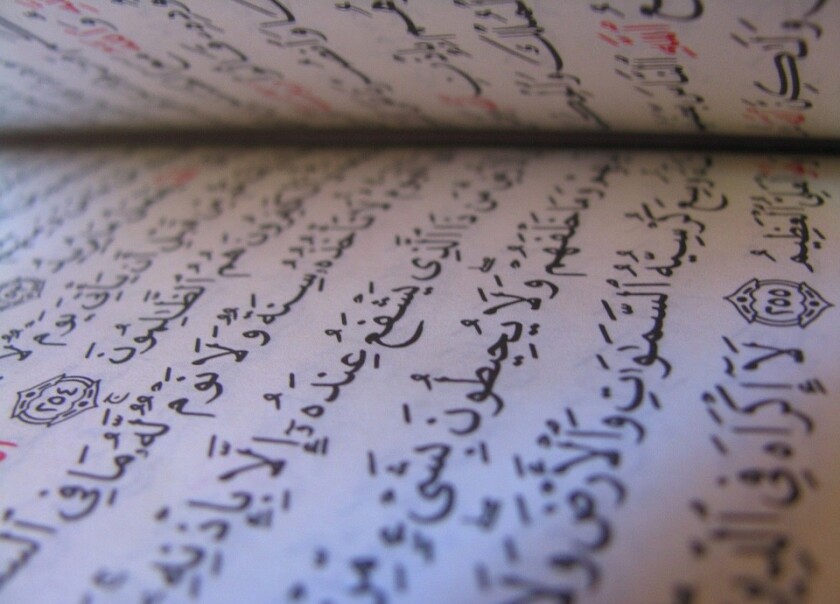

Sharia: Islamic teachings based on the Quran and other approved sources of the Sharia.

Sukuk: Certificates that represent a beneficial ownership interest in an underlying asset.

Takaful: Members contribute funds into a pool to secure against loss.

Wakalah: Agency contract. A customer appoints an agent to carry out business for them.

See also

Unlocking sukuk (IFLR magazine, March 2017)

DEAL: first Malaysian sukuk to monetise real estate project billings

Dana sukuk: why the market is overreacting

The three principles of Islamic finance explained